Mark 15:1-15 NASB

¹Early in the morning the chief priests with the elders and scribes and the whole Council, immediately held a consultation; and binding Jesus, they led Him away and delivered Him to Pilate.

²Pilate questioned Him, “Are You the King of the Jews?” And He answered him, “It is as you say.”

³The chief priests began to accuse Him harshly.

⁴Then Pilate questioned Him again, saying, “Do You not answer? See how many charges they bring against You!”

⁵But Jesus made no further answer; so Pilate was amazed.

⁶Now at the feast he used to release for them any one prisoner whom they requested.

⁷The man named Barabbas had been imprisoned with the insurrectionists who had committed murder in the insurrection.

⁸The crowd went up and began asking him to do as he had been accustomed to do for them.

⁹Pilate answered them, saying, “Do you want me to release for you the King of the Jews?”

¹⁰For he was aware that the chief priests had handed Him over because of envy.

¹¹But the chief priests stirred up the crowd to ask him to release Barabbas for them instead.

¹²Answering again, Pilate said to them, “Then what shall I do with Him whom you call the King of the Jews?”

¹³They shouted back, “Crucify Him!”

¹⁴But Pilate said to them, “Why, what evil has He done?” But they shouted all the more, “Crucify Him!”

¹⁵Wishing to satisfy the crowd, Pilate released Barabbas for them, and after having Jesus scourged, he handed Him over to be crucified.

Study

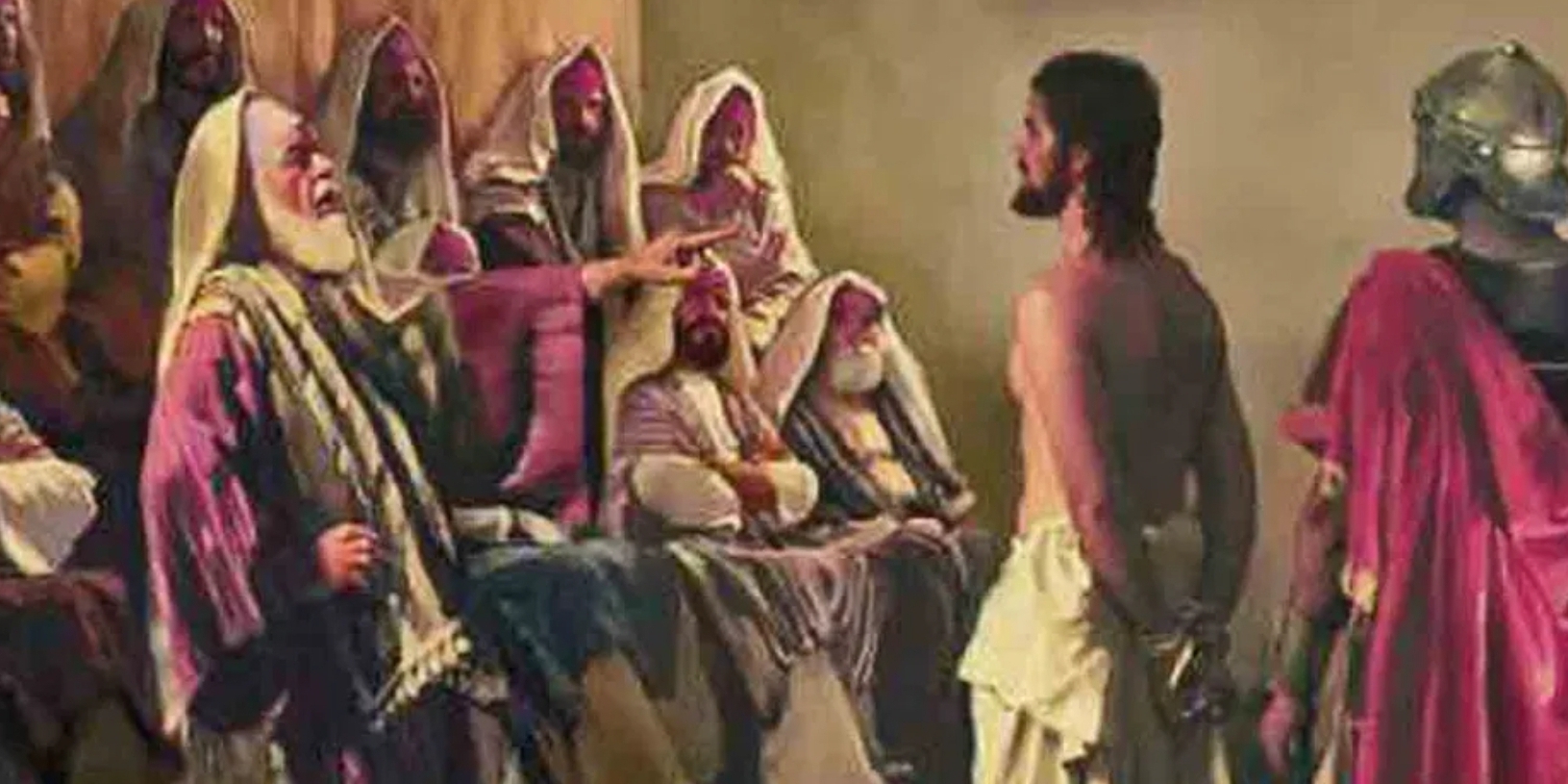

JESUS SENT FROM THE SANHEDRIN TO PILATE

FROM THE JEWISH TRIAL TO THE ROMAN TRIAL.

The first stage of the Jewish trial.

After the arrest at Gethsemane, our Lord was conducted back to the city, across the Kidron to the palace of the ex-high priest Annas, the father-in-law of Caiaphas, the actual high priest that same year.

The influence of this functionary was very great; his age, astuteness, riches, power, perhaps presidency of the Sanhedrim – all contributed to it.

In answer to the inquiries of Annas about our Lord’s disciples and doctrine, the Savior appealed to his teaching in the synagogue, in the temple, always in public; and referred him to his auditors on these occasions. This reply was construed into disrespect towards the ex-high priest., and resulted in the first act of violence, apart from the arrest itself; for one of the officers struck Jesus with the palm of his hand or with a rod (ῤάπισμα), as rendered in the margin. This was the first of the three stages of the Jewish trial.

a. Here we remark that both Jews and Gentiles took part in arresting Jesus, and conducting him to the high priest. “The band and the captain,” or chiliarch, that is, tribune, formed the Roman or Gentile element; while the “officers of the Jews” composed the Jewish element.

Thus from first to last “the Gentiles and the people of Israel” combined against the Lord and his Anointed.

b. The mention of both Annas and Caiaphas as high priests by Luke (Luke 3:9.) tallies with the fact that, owing to the arbitrary interference of the Romans, there might be several high priests alive at the same time; that is, those who had held the office and been deposed, and the person actually exercising the office.

Of course, according to the Law of Moses, there could only be one high priest at a time, and that rightful high priest was the hereditary representative of Aaron. Even in the Roman period the high priesthood had not become a yearly office, though the frequent depositions and displacements occasioned many changes and much confusion.

Thus Annas had been deposed in the twelfth year of our era by Valerius Gratus, the immediate predecessor of Pilate in the procuratorship of Judaea; yet, so great was his influence, that he had his own son Eleazar, his son-in-law Caiaphas, and four other sons subsequently appointed to the high priesthood.

c. The preliminary inquiry before Annas might elicit information with regard to the extent of discipleship, and so of sympathy among the rulers, as in the case of Nicodemus, that might be calculated on; not only so, it would result in a prejudgment of the ease through the shrewdness and influence of the ex-high priest.

Further, a higher object – an object most probably not dreamt of by either Annas or Caiaphas – was antitypical.

We read in Leviticus 16 that on the great day of Atonement, Aaron laid both his hands upon the head of the live, or scape-goat, and confessed over him all the iniquities of the children of Israel, and all their transgressions in all their sins, putting them upon the head of the goat; and sent him away by the hand of a fit man into the wilderness; and the goat bore upon him all their iniquities into a land not inhabited.

Similarly, the high priests concerned in this trial were, in the exercise of an analogous function, pronouncing sin to be upon the head of the Victim before he was led forth to crucifixion.

The second stage of the Jewish trial.

The second stage of the Jewish trial consisted of an informal investigation before Caiaphas, and a committee or commission of the Sanhedrim.

In order that a conviction might be obtained, it was necessary to secure two witnesses at least to depose to some definite charge. But while the testimony of some was irrelevant, that of others was self-contradictory. At length two volunteered to testify in the case. For this testimony, such as it was, they were obliged to travel back over a period of some three years.

Then, fixing on certain words of our Lord at the first Passover after entering on his public ministry, in reference to the temple, they either misunderstood them, or misinterpreted and consequently misrepresented them.

The words in question were constructed into contempt of the temple; this contempt, if fully proved, would have constituted a capital charge, just as, in the case of the protomartyr Stephen, the charge was that he ceased not to speak “blasphemous words against this holy place and the Law.”

But this charge was not substantiated; the evidence broke down in consequence of the disagreement of the witnesses. Our Lord had said, “Destroy (λύσατε) this temple, and in three days I will raise it up” (ἐγερῶ, a word quite suitable to resurrection, but no way appropriate to rebuilding); “but he spoke of the temple of his body.”

▪︎ One of the witnesses perverted this into, “I will destroy (καταλύσω) this temple that is made with hands, and within three days I will build (οἰκοδομήσω) another made without hands” (Mark 14:58);

▪︎ The other testified, “I can destroy (δύναμαι καταλῦσαι) the temple of God, and build (οἰκιδομῆσαι) it in three days” Matthew 26:61.

Accordingly, Mark adds, “Neither so did their witness agree.

What our Lord had spoken in a figurative sense they applied literally; for upraising they substituted building; what was really a promise they twisted into a threat; if they themselves destroyed their temple, he promised replacement.

The temple had long been distinguished by the Shechinah glory or visible presence of God, yet was doomed to destruction; the human body of Jesus, in which dwelt the fullness of the Godhead bodily, when raised up would supersede the inhabitation of God in the literal temple.

Pretence of legality.

What can the members of the Sanhedrim present on this occasion?

They wish to keep up the semblance of law and justice, but the evidence has significantly failed.

The condemnation of Jesus is a foregone conclusion, in whatever way it is to be effected, and still the appearance of legality must be maintained.

A clever thought occurs to the mind of the high priest, and in default of evidence he resorts to the desperate expedient of causing Jesus to criminate himself.

Accordingly, standing up into the midst (εἰς μέσον), and thus passing from his seat to some conspicuous position, as Mark graphically describes it, he adjured Jesus most solemnly to declare if he were indeed the Messiah, that is, “the Christ, the son of the Blessed,” viz. if he claimed to be not only the expected Messiah, but also to be a Divine person – the Son and equal of God.

Whereupon followed the avowal by which he criminated himself, and gave ground of condemnation. Though He had acknowledged the confession of Peter to the same effect, and even commended it; though He had accepted the same or an equivalent title on the occasion of his public entry into Jerusalem , He had not as yet publicly claimed it.

Now, however, He avowed it in the most public manner, in the presence of the high priest and members of council. According to Mark, this avowal was expressed by “I am;” according to Matthew by “Thou hast said;” while in Luke’s report of the third Jewish trial, the two are combined with a trifling variation, namely,” Ye say that I am.”

Hypocrisy in high places.

If our Lord had remained silent, they would have probably charged him with imposture; now that he confessed his Messiahship and future exaltation, they proceeded to condemn him for blasphemy.

The council sought nothing further; they wanted only evidence against him – something to inculpate, not to exculpate, him.

They did not wish to hear the grounds of his claim; they wanted no explanation.

With the Jews the setting up of a claim to any Divine attribute was regarded as blasphemy; the claim of Christ, according to their opinion of him, came under the Mosaic law of blasphemy.

And now the hypocrisy of the high priest is something shocking.

As the highest ecclesiastical functionary of the nation, and the principal officer of its great council, his duty surely was to investigate the confession and claim of one who professed to embody the hopes of the nation, and to scrutinize the true nature of that claim, the real meaning of it, the grounds on which it rested, the reasons of it, and the evidence for it.

On the contrary, he grasped with avidity at the prospect of a condemnation.

His sense of justice was no higher than his sense of religion; on anything that might tend to explain, or extenuate, or exculpate, he shut his eyes and closed his ears.

But what is still more disgusting in the conduct of this ecclesiastic was his abominable hypocrisy.

He feigned abhorrence at the crime which he was so anxious to establish. Glad as he was to have this constructive crime of blasphemy to allege, he pretended the most extreme horror by tearing his garments from the neck to the waist. Here, indeed, was “spiritual wickedness in high places.”

The third stage of the Jewish trial.

This was the more formal trial; it was held at dawn of day, and in the presence of the whole Sanhedrim (ὅλον τὸ συνέδριον).

The previous trial, being held at night, was invalid; besides, it had been conducted only by a representation – an influential representation or committee of the Sanhedrim, consisting, it is probable, mainly of the priests.

At the present stage the whole council was present, with its three constituent parts – elders, chief priests, and scribes.

This is the meeting of council mentioned in Mark 15:1, and in the parallel verses of Matthew and Luke, viz. Matthew 27:1 of the former, and Luke 22:66 of the latter.

The object was to ratify a predetermined decree. They also found it necessary for their purpose to change the charge, and consequently also the venue.

It was more, perhaps, with the object of consummating than of ratifying their sentence that this meeting was hastily summoned. The judicial murder which they had decided on was not in their power to carry out. Had it been so, stoning would have been the death-penalty.

A deputation of an influential and imposing kind waited upon Pilate, to whom the Prisoner is now transferred, either hoping, through the facile condescension of the procurator, to get the case remitted to themselves for execution, or to devolve it on the Roman governor.

THE ROMAN TRIAL,

OR TRIAL BEFORE PILATE.

Incidents leading to the crucifixion.

Crucifixion was a mode of death unknown to Jewish law, and unpractised by the Jewish people. It was fearfully familiar as a mode of execution among the Romans – this we learn from their writings; as, “Thou shalt not feed the crows on the cross,” of Horace; “It makes no difference to Theodore whether he rots on the ground or aloft, i.e. on the cross,” of Cicero; also from such expressions as the following: – “Go, soldier, get ready the cross;” “Thou shalt go to the cross.” It was not, however, till the Roman period that it was introduced into Judaea.

It was only after Jew and Roman had come into collision, and had taken respectively the position of conqueror and conquered, of sovereign and subject, that this cruel mode of death found its way into the Holy Land.

And yet, strange to say, long years before the Romans had risen to pre-eminence and power, and centuries before Judaea had been catalogued as a province of their vast empire, it had been foretold that Messiah’s death would be by crucifixion.

We refer to the well-known prediction in the twenty-second psalm, where we read, “They pierced my hands and my feet” (“piercing my hands and my feet,” according to Perowne; “geknebelt” [‘fastened,’ as the extremities were in crucifixion] meine Hande und Fusse,” according to Ewald).

Before that prophecy was fulfilled a long series of events had to be evolved; dynasties had to rise and fall; a kingdom had to pass through the hands of many successive rulers and become extinct; an empire, the greatest of ancient times, had to rise to unprecedented power; that kingdom had to be absorbed, and become a province of that empire. In a word, Judaea had to become tributary and Rome triumphant before the event could take place.

The facts referred to changed the complexion of our Lord’s trial.

Of the many charges they might have manufactured, such as violation of the sabbath law, contempt of oral tradition, purification of the temple, heretical teaching, or esoteric doctrines of a dangerous kind., they elected that of blasphemy, grounded on His own confession of divinity, or of being “the Son of God;” while He strengthens the admission by foretelling that, besides (πλὴν) the verbal avowal, they would have ocular proof when they should see him – the Son of man as well as Son of God – “sitting at the right hand of power, and coming on the clouds of heaven.”

This admission was, as we have seen, extorted after the suborned witnesses had entirely broken down, and the two best of them had shamefully perverted and prevaricated; but, notwithstanding, it was seized by the high priest from his false notions of Messiah as an acknowledgment of the charge preferred.

Stoning was the mode of death which the Law appointed for that crime; but though the Jews could pass sentence, they could not execute it. One of the signs of Messiah’s advent thus stared them in the face; “the scepter had [thus] departed from Judah, and a lawgiver from between his feet.”

Accordingly, they were obliged to have recourse to the Roman procurator, Pilate; but then they knew that he would not interfere with their religious controversies. What now is to be done? They take new ground; they change the accusation from blasphemy to treason, in order to subject their Prisoner to the secular power.

Charges preferred.

The charge was really constructive treason, but their indictment as first advanced consisted of three articles.

They charged him

▪︎ with perverting the nation;

▪︎ with forbidding to give tribute to Caesar; and

▪︎ with affirming that he himself was Christ, a King.

Pilate pays no attention to the first and second, and only notices the third.

His mode of procedure was in accordance with the Roman respect for law and sense of justice.

He refused to confirm the sentence of the Sanhedrim, and proceeded to hold a private and preliminary examination (ἀνακρίσις: as we read in Luke 23:14, ἀνακρίνας), having removed Jesus into the Praetorium, or governor’s palace.

This examination Pilate conducted in person, as he had no quaestor; and was satisfied of the harmlessness of the title of King by the Savior’s explanation that his kingdom was not of this world.

Pilate was convinced of our Lord’s innocence, but hearing Galilee mentioned, he at once caught at the idea of shifting the responsibility, or at least sharing it with Herod Antipas, and at the same time of conciliating the tetrarch by an act of courtesy; and in consequence remitted (ἀνέπεμψεν) the accused to Herod’s as the higher court, or technically from the court apprehensionis to the court originis.

Herod, having been disappointed by seeing no miracle performed by the reputed miracle-worker, and dissatisfied by his dignified silence, sent him back to Pilate, arrayed in a white or gorgeous (λαμπρὰν, from λάω, to see) robe, thus caricaturing his candidateship or claim to royalty, and thereby hinting to Pilate that instead of a punishable offense, it was rather a matter of contempt and ridicule.

Pilate is perplexed, and no wonder; his vacillation now begins to take effect.

▪︎ He sins against his sense of justice as a Roman magistrate;

▪︎ he sins against conscience;

▪︎ he proposes a most unjust and unlawful compromise, namely, the chastisement (παιδεύσας) of an innocent person.

But this concession, unrighteous as it was, did not satisfy; and again he tried to avail himself of the custom of releasing one at the feast in compliance with the clamor of the multitude; but the cry of the populace, instigated by the agents of the priests, was, “Not this man, but Barabbas.”

By a symbolic act, this weak judge seeks to transfer the guilt to the infuriate mob, and still clinging to the hope that the multitude would be content with a compromise, he delivered Jesus to be scourged, and that, not with the rods of the lictors, but with the horrible scourge tipped with bone and lead (φραγελλώσας).

Retrospect at the indignities.

The first act of insult and violence was, as we have seen, during the inquisition by Annas, who sought to entangle him by insidious interrogatories, when one of the officers struck Jesus with his hand or with a rod (ῤάπισμα), as John informs us.

The next was in the course of the second Jewish trial, which was conducted by Caiaphas, and by which the confession of being “the Christ, the Son of God,” was extorted. In describing this sad scene, no less than five forms of beating are mentioned by the Evangelists Matthew and Mark and Luke.

The latter has

▪︎ δέροντες, properly to skin or flay, and then beat severely;

▪︎ ἔτυπτον, imperfect, they kept smiting him;

▪︎ παίσας, to inflict blows or strike with violence; St. Matthew has

▪︎ ἐκολάφισαν, they buffeted with clenched fist; and

▪︎ ἐρράπισαν, they struck with open palms or rods; while Mark has ῤαπίσμασιν… ἔβαλλον, they received him with blows of the hands or strokes of rods.

It was on this occasion they did spit in his face and blindfold him, derisively bidding him “prophesy, who is it that smote thee?” with many other vilifications, in some or all of which the members of the council, as well as the menials of the court, took part.

We now hasten from such a disgraceful scene – from the scornful spitting, the shameful scoffing, the savage smiting, the ribald revilings, the shocking cruelties, and the savage barbarities of the miscreants of the Sanhedrin – and pass on to his treatment by Herod.

He joins with his men of war in setting him at nought and mocking him, and arrays him in a gorgeous robe, as if to caricature his pretensions, or, as some think, a bright or white robe, as though in mimicry of his candidature for royal honors.

Thus sent back to Pilate, he is scourged by the procurator’s command.

The very thought of that scourging makes the blood run cold and the heart sick.

All that preceded, cruel as it was and devilish as it was, caused but little of bodily pain as compared with the scourging.

▪︎ He had indeed suffered dreadfully, in both body and mind.

▪︎ He had been betrayed by one disciple, denied by another; three slept when they should have sympathized; at length all forsook him and fled.

▪︎ He has been hurried from one tribunal to another – from the Sanhedrim to the Roman governor, from the Roman governor to the Tetrarch of Galilee, and from Herod back to Pilate.

▪︎ See him the night preceding in the Garden of Gethsemane, in the midst of his agony, when perspiration bathed his body, and that sweat trickled in big drops down to the ground.

▪︎ See him now in the place where he is scourged, cruelly scourged, his face marred, his body mangled, the quivering flesh fearfully torn with the bits of lead and bone plaited into the leathern thongs, while he is still barbarously smitten, and savage stripes inflicted on him.

▪︎ See him again, surrounded by a band of ruffian soldiers – provincial or rather Roman soldiers, to their disgrace be it recorded – who plait a crown of thorns, and press it down so that the sharp and prickly points more painfully pierce his temples and lacerate his bleeding brows.

▪︎ While his body is still smarting from the wounds made by the scourging,

▪︎ while the blood is still running down on every side from the thorn-crown,

▪︎ while insult is being heaped on insult and added to injury, they smite his sacred head with a reed as if to gash that head more brutally, and leave the thorns yet deeper in the skin.

One other act in that bloody tragedy precedes and prepares for the crucifixion itself.

Instead of the gorgeous or white robe with which Herod and his men of war had, in their bitter mockery, clothed him, the Roman soldiers of the governor arrayed him with the military scarlet or purple war-cloak, mimicking the imperial purple.

He is stripped a second time – the mock-garments are pulled off him, and his own put on; and thus all his wounds are opened afresh and their pain renewed.

During the mock-coronation, in which the leaves of thorn burlesqued the imperial wreath of laurel, the reed the royal scepter, and the soldier’s cloak the emperor’s purple, they spat upon him, they smote him on the head,, they bowed the knee in mockery, and they scoffed him, saying,” Hail, King of the Jews!”

Pilate’s last effort to release him.

Once more Pilate makes another effort to prevent the crucifixion of Christ.

Though scourging was usually the frightful preparation for crucifixion, yet Pilate is most anxious to proceed no further. He seeks to have it regarded, perhaps, in the light of trial by torture without anything worthy of death being elicited, or perhaps he wishes to have it accepted as a sufficient substitute for crucifixion.

With some such purpose – a purpose, as it is generally and properly understood, of commiseration – he exhibits the Savior in that unspeakably sad and sorrowful plight – worn, wan, and wasted; his features here befouled with spitting, there besmeared with blood; his face disfigured by blows – marred more than any man’s and his countenance more than the sons of men; while blood-drops trickle from his many wounds down on the tesselated pavement, lie calls their attention to this woebegone and most pitiable spectacle, saying, in words that have thrilled many a heart, and shall thrill thousands in the generations that may be yet to come, “Behold the Man!” But in vain.

The only response was a louder, sterner, fiercer cry: “Crucify him! crucify him!” He deserves to die, “because he made himself the Son of God.” Moved to the inmost depths of his being, Pilate struggles on for his release; but, amid the loud clamor for the Victim’s blood, there are ominous growls that boded a possible impeachment on the charge of treason against the governor himself. “If thou let this man go, thou art not Caesar’s friend;” “We have no king but Caesar.”

Shame upon those bloodthirsty hypocrites who could say so; though they hated Caesar and all his belongings, and ‘were real rebels at heart!

And shame upon that cowardly judge, who, as a Roman magistrate, quailed before such cruel clamor, and had not the courage of his own certain convictions!

Agencies co-operating to compass the crucifixion.

If we glance for a moment at the various influences that were at work to compass our Lord’s death upon the cross,

▪︎ we find in the foreground the envy and malice of chief priests and rulers;

▪︎ the mean-spirited avarice of the wretched traitor Judas;

▪︎ the want of firmness and thorough conscientiousness on the part of Pilate;

▪︎ the fury of a fickle mob misled by designing demagogues;

▪︎ the submission of the soldiers to the orders of their superiors;

▪︎ all obeying the propensities of their own nature, though ignorant of the reason or the results;

▪︎ all fulfilling the predictions of Scripture, though not knowing it;

▪︎ and all accomplishing the purposes of God, though not intending it.

But in the background, as we shall see in connection with the crucifixion itself,

▪︎ it was sin on the part of man,

▪︎ and substitution on the part of the Savior.

“He bore our sins,” says the apostle, “in his own body on the tree.” It was determinate counsel and foreknowledge on the part of God. In accordance with that counsel and foreknowledge, and in consequence of our sin and the Savior’s substitutionary self-sacrifice, “ought not Christ to suffer these things?” Was it not necessary for him to become “obedient unto death, even the death of the cross”?

Twitter: @SchoemakerHarry

Website 1: https://devotionals.harryschoemaker.nl

Website 2: http://bijbelplaatjes.nl